Making a Living

I have made my living as a -

what do you call it? - computer programmer, software

engineer, systems analyst - from 1987 to 2017.

______________________________________________________________________________________________

Here I am, an IRS employee, getting an award in 1987.

At left is the Director of the Kansas City Service Center, and at right is the Commissioner for the Midwest Region.

This award is for a computerized worksheet package I created on my own time at home,

which was accepted for nationwide use in the Underreporter Program.

The amount of the award was the largest ever given by the IRS for an employee suggestion.

Here I am, an IRS employee, getting an award in 1987.

At left is the Director of the Kansas City Service Center, and at right is the Commissioner for the Midwest Region.

This award is for a computerized worksheet package I created on my own time at home,

which was accepted for nationwide use in the Underreporter Program.

The amount of the award was the largest ever given by the IRS for an employee suggestion.

Say what you want about the government, but I observed that it's a better-managed organization than most private employers,

its employees are for the most part dedicated and conscientious, and a talented and hard-working person can do well.

This was the last big thing I did at the IRS. I regret resigning.

Here is an article about software I created for the Criminal Investigation Branch at the Kansas City Service Center in the early 1990s.

The program I created went into use in all ten service centers, and again, I received a sizeable award for my work.

Some observations on my career, and the state of

the workaday world in general.

My career did not get easier. Oh, the work itself didn't change a great deal; it was still a matter of figuring out how to make a machine do what you want it to, and then doing it. The capabilities of the machines have grown, and the languages one uses to communicate with the machine have evolved, so it is challenging to stay abreast of technological advancements.

But that's not the hardest thing. The hardest thing is finding a good job and keeping it. With a few exceptions, like government work (and even that's increasingly going to contracting), permanent jobs are rare in the field. Management seems to have decided that IT people are a commodity, to be replaced like tires on a car.

It makes sense to use contractors for projects which have a beginning and an end, but I don't understand paying a contractor a large wage for work which is needed for the foreseeable future. The company is really paying another company, which then pays the contractor. If the contractor makes $45/hour, the cost to the company is more like $80/hour. Doesn't the company realize that letting someone go means a loss of knowledge and competence, and that it's more cost-effective in the long run to hire someone as a direct employee who will be there for years?

Best example: I worked at Monsanto on contract for five years, doing significant things and gaining a lot of knowledge about the business and its procedures. After about 4-1/2 years, it became obvious that the people in the boardroom planned to "cut costs" by getting rid of us American contractors and bringing in lower-cost contractors from India, and we were expected to train our replacements. I suspect this decision was related to Monsanto's desire to sell itself to Bayer AG. I mean no disrespect to foreigners, but I found that many of these new contractors could not speak English and had very little concept of how to do the work. I wonder how that worked out after I left...

Since I was laid off from Cellnet in 2004 (again, cost-cutting in preparation for acquisition by another company), I have had done work for:

Yellow Roadway, Overland Park

AMC Entertainment, Kansas City

State of Tennessee, Nashville

"Permanent" job with Materialogic, Olivette, MO

BJC Healthcare, Brentwood, MO, rewriting old server code

Wells Fargo Advisors, St. Louis

Magellan Health Services, St. Louis Country

Commonwealth of Virginia, remote from Chesterfield, MO, creating procedures to load Medicaid claims into a data warehouse

Monsanto, Creve Coeur, MO, applications DBA

Enterprise Holdings (car-rental company), Weldon Springs, MO

In 2017, I went from Enterprise to Charter Communications (now Spectrum) in northwest St. Louis County. After three months, I was offered a *permanent* position with Charter, good pay and benefits. My second day in that permanent position, my mother died in an automobile accident. She had named me as executor of her estate, which was comfortably-but-not-extremely sizable. I went to a meeting at work the next day where silly stuff was being contemplated, and I had an epiphany: I don't have to do this anymore. So ... I retired! Thanks, Mom!

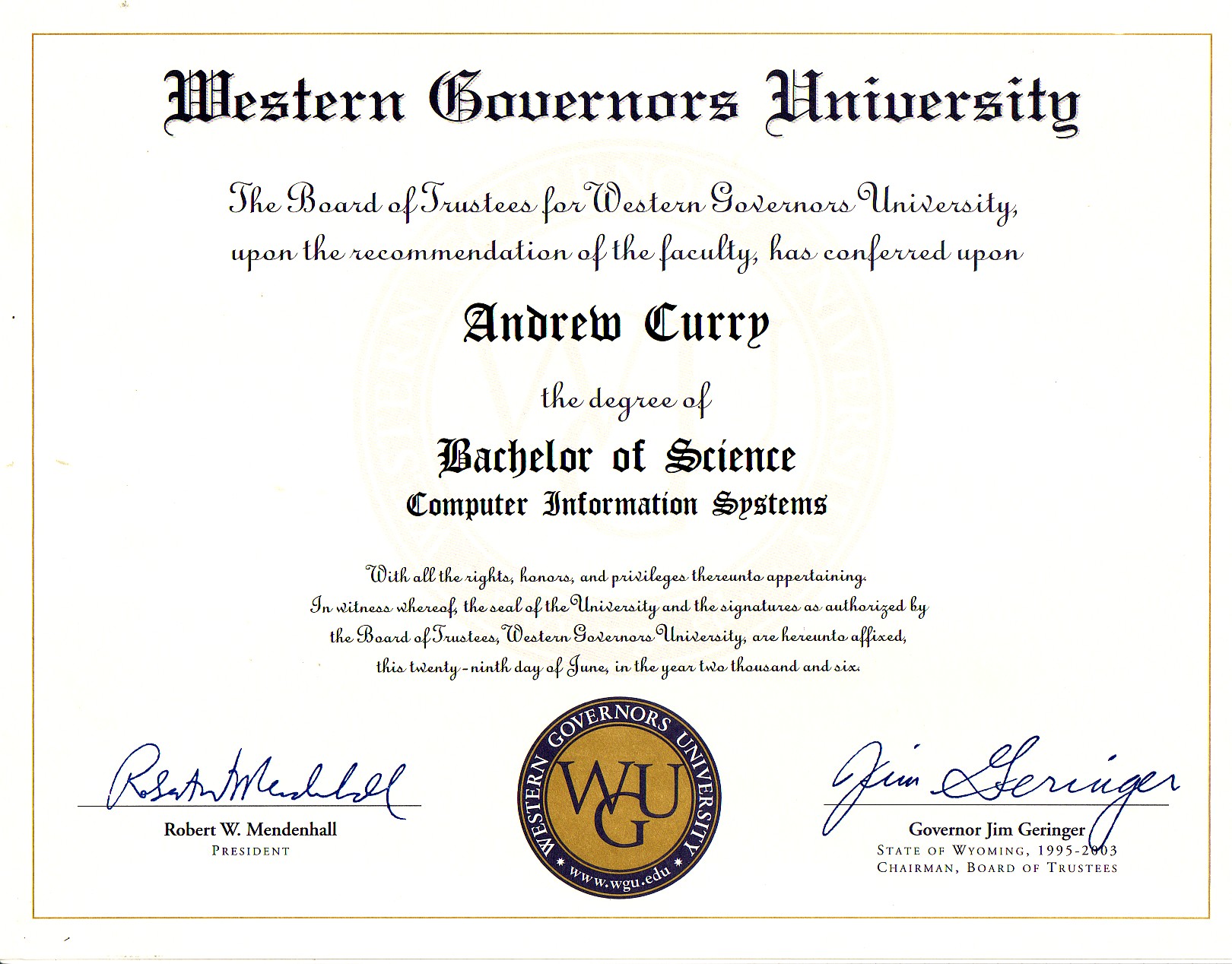

In the early

2000s, I noticed that job postings in my field were

increasingly requiring a Bachelor's degree.

Seeing the writing on the wall, I got the degree that I had started on at the University of Kansas in 1968.

In fact, this website was my "Capstone Project."

Seeing the writing on the wall, I got the degree that I had started on at the University of Kansas in 1968.

In fact, this website was my "Capstone Project."

Copyright 2006, 2013, 2022 by

Andy Curry